June 7, 2005 marks twenty-five years since my Dad passed away. It seems impossible but I miss him more each year. He was a great listener as well as a fascinating raconteur. He had a very warm persona, treating everyone he came in contact with as though they had something special to say and often they did. His curiosity in his fellow man came across as being genuinely interested in all people. He was generous in every way, from sharing his home, giving to anyone who asked for money (if he had it), he gave his watercolors away, happy that they were admired. He had many friends throughout his life that were true lifelong relationships. He was a loyal friend. He loved to laugh and share meals and wine, always exchanging ideas about literature and art. He truly enjoyed life and made the world a better place by his wholehearted embrace of the world. He was tolerant, kind, inspiring, droll, genuine, loving, intelligent, thoughtful, a wonderful combination of many talents, humble as well as proud.

I love you Dad,

Your daughter,

Valentine

If you would like to have your Henry Miller tribute added to this page please contact: val@henrymiller.info

Wow. Twenty five years! Time flies. Time moves on. Time is nothing. Time is all. I don't know any more. When I was fifteen, twenty one seemed a mile or more away. Now, I am fifty six and time has zipped passed me so quickly, I never even felt it.

But time stopped on June 7th, 1980. It stopped with a bad phone call. It stopped because I knew what the phone call was before I picked up the receiver. It stopped because the voice on the other end confirmed what I already knew. Dad was dead. Not any more alive. Dead. Not living. Dead. Not talking, dead. All dead.

I know many people that have lost loved ones. All sad. All of them sending people into places they have never been, for the most part. It is something one becomes a bit accustomed to. But this was different. Very different.

Inside my brain, I almost laugh at the Obits I read from time to time. Every Mom, every Dad, states that there son or daughter, or best friend was the Greatest!!! Always. Ever read an Obit with someone saying there child was a jerk, a born felon, a criminal, a worthless person??? NO!!

But most people are just that. People that pass on. Be it by accident, murder, War, whatever. Just another body, going through some biological process… Moving through the process of inert, to alive, to dead… A few people say goodbye, so long, and guns are fired, people weep, and so it goes. And we all move on.

Not this time. My father actually meant something to the World he lived in… He actually contributed something genuine and good to the public. He gave all of himself to help something more than his Family or friends. He gave his life, to Art and made Art out of his life.

All the press about Cancer or Sexus, or Murder the Murderer, says nothing about the man that wrote those books or stories. He was one person that I could say, was better in person, even, than his books. And I met many of his contemporaries. No one stood a candle to him.

He knew more about being alive, being a person, being a human being, than anyone that I have witnessed. I put him on the scale of Ghandi, Mandela, Ali… He didn’t make speeches, he spoke to you… To your heart and desires. He spoke to your inner self that was striving to escape the bonds of parenthood, childhood, social mores, and Nationalism… There is no doubt why he loved France. More even than his own country in some ways.

My country, my father’s country, is so full of hypocrisy, he had to leave for awhile. It was never because he hated it. It was for the very best of reasons… It failed to live up to what it could have been. It betrayed him… It betrayed me… It has betrayed all of us.

There are no voices left in this country. So honor those that spent their entire lives trying to tell it how to uphold its potential… Because now, there are nothing but greed and powermongers left… And they are killing us and the rest of the world. Heed some oldtimer’s advice.

The greatest gift that a man, a father, can pass on, is interest. To be astounded by what has already happened, and to look forward to a bright future. We are all dead here now.

Always Merry and Bright… Don’t You Know? HMMMMMMMMMMMM!!

Tony Miller May 2005

Here is an artist who reestablishes the potency of illusion by gaping at the open wounds, by courting the stern psychological reality which man seeks to avoid through recourse to the oblique symbolism of art. Here, the symbols are laid bare, presented almost as naively and unblushingly by this over—civilized individual as by the well—rooted savage. It is no false primitivism which gives rise to this savage lyricism. It is not a retrogressive tendency, but a swing forward into unbeaten areas.

– ANAIS NIN’S Preface to the first edition of Tropic of Cancer

Henry is like a mythical animal. His writing is flamboyant, torrential, chaotic, treacherous, and dangerous. Our age has need of violence I enjoy the power of his writing, the ugly, destructive, fearless cathartic strength. This strange mixture of worship of life, enthusiasm, and passionate interest in everything, energy, exuberance, laughter, and sudden destructive storms baffle me. Everything is blasted away: hypocrisy, fear, pettiness, falsity. It is an assertion of instinct. He uses the first person, real names; he repudiates order and form and fiction itself. He writes in the uncoordinated way we feel, on various levels at once.

It is an effort to transcend the rigidities and patterns made by the rational mind. He can be swept off his feet by a book, a person, an idea. He is a musician and a painter. He notices everything. He selects from everything only what can be enjoyed. He finds joy in everything.

– “The Diary of Anais Nin” volume one, 1931-1934

I suspect that Henry Miller’s final place will be among those towering anomalies of authorship like Walt Whitman or William Blake who have left us, not simply with works of art, but a corpus of ideas which motivates and influences a whole cultural pattern.

– LAWRENCE DURRELL –

There is nothing like Henry Miller when he gets rolling. One has to take the English language back to Marlow or Shakespeare before encountering a wealth of imagery equal in intensity.

– NORMAN MAILER –

Most of us,

quite a lot of us anyway,

use four letter words.

I know most men do.

Usually they don’t

when there are women around,

which is hypocritical,

really.

Words can’t kill you.

The people that banned words

in books didn’t stop people

from buying those books.

If you couldn’t buy Henry Miller

in the early sixties,

you could go to Paris or England.

We used to go to Paris,

and everybody would buy Henry Miller books

because they were banned,

and everybody saw them,

all the students had them.

I don’t believe words can harm you.

– JOHN LENNON – On Censorship And Henry Miller

To The Dean

What should I say of Henry Miller:

a fantastic true-story of Dijon remembered,

black palaces, warted, on streets

of three levels, titled, winding through

the full moon and out and

down again, worn-casts of men: Chambertin-

This for a head

The feet riding a ferry

waiting under the river side by side

and between. No body. The feet

dogging the head, the head bombing the feet

while food drops into and

through the severed gullet, makes clouds

and women gabbling and smoking, throwing

lighted butts on carpets in department stores,

sweating and going to it like men

Miller, Miller, Miller, Miller

I like those who like you and dislike

nothing that imitates you, I like

particularly that Black Book with its

red sporran by the Englishman that does you

so much honor. I think we should

all be praising you, you are a very good

influence.

– WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS –

I consider Henry Miller important for many reasons. First of all, he’s a mighty good writer. In this epoch when many writers play around with words instead of observing life with all its mysteries and complications, Henry Miller is a man who gets inspiration first hand, or from the first well. It is not the words which are important to him, but what is behind them. His life and his writing cannot be separated in any way. The reader recognizes Henry Miller in every line of his works.

Henry Miller had also the courage and idealism to fight for literary freedom. He did it almost single-handedly. He was banned for years and excommunicated from the literary establishment. But he kept on fighting for what he considered just. And when victory came he allowed others to enjoy the spoils and in this respect he became a literary leader of the highest magnitude. The fear of censorship has left literature. Every writer can say what he wants and the way he wants nowadays.

As a person, Henry Miller is completely sincere, straightforward and as far from politics as a man can be. Although I don’t write in his style, I cherish him as a writer and as a friend of everything which is genuine in the art of writing.

– ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER –

Those who criticized him, those who—to the end—denied him his place in the pantheon of poets—were in part, unknowingly, reacting to the fears his honesty roused in them.

He was a heartbroken lover of mankind, a naïf pretending to be a cynic. “Just a Brooklyn boy…” he often said of himself.

He was the most generous writer I have ever known (and I have known one or two who, in their generosity, flouted the general rule that writers hate all other writers, except the safely dead).

– ERICA JONG –

What Miller did articulate was the disgust, the contempt, the hostility, the violence, and the sense of filth with which our culture, or more specifically, its masculine sensibility, surrounds sexuality.

– KATE MILLETT –

Where Henry Miller is especially great is in his descriptions of endearing human figures that he has met all over Europe and America, and in his profound mystical interpretation of certain landscapes and towns into whose souls he burrows, reaching a point of perception almost Shakespearian.

– JOHN COWPER POWYS –

In his Introduction to the first Grove Press Edition of Tropic of Cancer (1961), the poet and critic Karl Shapiro said of Henry Miller, “Everything he has written is a poem in the best as well as in the broadest sense of the word… If one had to type him one might call him a Wisdom writer.”

Miller’s wisdom is, in his own words, “The Wisdom of the Heart.” Miller wrote without artifice, from the center of his being, and this is what draws me to him. There is no persona, no voice, no mask, to distance the reader from the author. The author, Henry Miller, is on the page, exposing himself for all to see. And what does he expose? His humanity, his faith in individuals, his love for life, his resistance to systems and structures that diminish the human spirit. One reads Miller, and one immediately feels in friendly company, as though encountering him on a street corner, or in a café. Miller is accessible, available to us all, to anyone who can read and understand a simple letter from a family member or a friend. I am going on too long. Pick up one of his books and enjoy his company for yourself.

– ARTHUR HOYLE –

Like many others, I recognized the name Henry Miller as the American writer, a man ahead of his time who lived the bohemian life in Paris – and who tangled with censorship and obscenity laws. This changed, however, when I happened upon him in a completely different context. During the early stages of my research on George Dibbern, a man about whom I was simply curious because his book Quest was so hard to come by, I discovered the review of Quest Miller had written for Circle in 1945. It ended with a note stating that he had bought up all remaindered copies to sell and that the money collected would be sent to Dibbern to get him sailing again, once he was released from internment camp in New Zealand. What did the famous Henry Miller have to do with the obscure George Dibbern, I wondered.

I learned that in the Miller Collection housed at UCLA were 107 items of correspondence relating to Dibbern and his family. On reading those letters it became clear to me that there was far more to Henry Miller than I had ever imagined. His commitment to helping out strangers, to encourage and to cheer – when he himself was overworked, overwrought and living in poverty – frankly amazed me. After reading Quest in 1945 he wrote to the author “as a brother”, so closely did he identify with him and his vision of a world of peace and brotherhood, a world without borders. Thus began a friendship by correspondence which lasted till Dibbern’s death in 1962.

Miller, in his generosity, offered assistance and friendship to the entire Dibbern family. He promoted Quest every chance he could and wrote to friends urging them, – “I earnestly beg you” were his words – to buy the book. Relentlessly he hounded the American authorities to speed up royalty payments, withheld because Dibbern was considered an enemy alien. He tried repeatedly to initiate a reprint of Quest as well as new editions in translation. He rallied neighbours and friends in Big Sur to join him and Lepska in sending food and clothing parcels (when they themselves had so little) to Dibbern’s wife and daughters, starving and struggling to survive the devastation of post-war Germany. He sent out appeals for donations from his many contacts to help Dibbern refit his boat after a sailing disaster; offered to lend money to the financially strapped sailor, though he himself had none to spare; wrote endless letters in the attempt to find a publisher for Dibbern’s second manuscript. He was instrumental in bringing about the German edition of Quest which appeared after Dibbern’s death and for which he wrote the preface. Throughout, he offered encouragement and moral support. All this for a man he never met!

The words of the Dibberns themselves (excerpted from letters to Henry Miller) reflect their gratitude and the high regard in which they held their American friend.

George Dibbern:

“You see my faults and weaknesses without losing faith in me nor in my sincerity.” [Sept. 25, 1945]

“Dear Henry, what a friend you are! I think you are a kind of angel or reassuring pilot whose letters of cheer always come at the very moment I need them most.” [July 22, 1947]

“Dear Henry, brother captain, Many, many thanks for your letter. Though I am right again I am still so that I do appreciate the warm hand of a brother who knows.” [Aug. 12, 1954]

“You are a marvel! There you are working eyes out on big books of your own and still have time for no end of other people who are really unimportant like us here. How can we thank you?” [June 14, 1956]

Elisabeth Dibbern (George’s wife):

“I can’t tell you how we were glad to receive your friendly and cheerful letter […].

We are so disaccustomed to any friendship, kindness and glad tidings that we can scarcely believe

that anyone should wish to help us. We have suffered so much and we have been so hopelessly delivered

to grief and troubles that I could not imagine that an entirely strange American like you should

want to help me only because of reading my husband’s book.” [Dec. 3, 1946]

Frauke Dibbern (George’s daughter):

“My sister and I are awfully glad to hear of my father through you and then to be asked,

what we are needing. We are feeling Christmas coming and danced at first up and down like Red Indians.” [Oct. 17, 1946]

As for me, I am indebted to Henry Miller for having saved the Dibbern-related correspondence. Once I read the material, I was hooked: the fascinating story of George Dibbern’s life and of the Miller-Dibbern friendship was waiting to be told. The undertaking absorbed almost ten years of my life, connected me with books, people and places I would otherwise never have encountered – and has resulted in the recent publication of Dark Sun: Te Rapunga and the Quest of George Dibbern. For that I have Henry Miller to thank!

Erika Grundmann

Manson’s Landing, BC

May 2005

Letter to Henry, May, 2005

Dear Henry,

Life goes on as you transcended it about 25 years ago. I would like to think that your spirit transcended beyond flesh. You are so much to so many, but more than anything else, you lived, experienced and interacted. We never met, but I feel that I’ve heard you in many ways.

When you shared the journey of your life and your passion for living in Tom Shiller’s film Henry Miller Asleep and Awake, I knew there was an immense depth in you. You never stopped experiencing life. Life as it is, out there, the abundance, the poverty, sensuality, joys, disgust and suffering. You pointed out the decay of our modern world. Reading took on a new dimension then, not just titillating, but a chronicle of a complete life. This was a process that worked for you. You freed yourself.

I pay tribute to you, via the books that I collect. Yours is the largest of my collections. In 1985 I got a box of about 25 first editions from Dan Flanagan. With the encouragement of fellow collector Jon Tatomer, that seed has grown and I now have 1,000 different printings, proofs and associated items of your work. These will be part of the Henry Memorial Library in Big Sur once their archive room is completed. I also have hundreds of pieces of ephemera and books with prefaces, contributions or quotes. It continues to grow. As more of your editions come out, there is no end in sight.

In 1993, I made contact with Roger Jackson, who was working on a bibliography of your work. There was trust, with a flow of information that I felt was truly in the spirit of Miller. We wrote and interacted for two years, building on the known volumes of your work. That work continues. He was a friend before we actually met. I’m sure you had many such friends. And when we did meet, what an occasion. I understand how you cherished your friends and found much fulfillment and joy from your associations. My sense is that most of the time you worked hard at your writing. Although you talk at times of the nobility of laziness, you always corresponded and Anais thought that you worked too much.

I love your associations with Anais, Norman Mailer, Erica Jong and so many artists and writers.

I love Reflections which contains your thoughts on many subjects. I guess you never met Gurdjieff, but I also reflect on the concept that within the body are many personalities. Knowing them and becoming aware of them. You continued to learn, seek, and love until the end.

Thank you,

William Ashley

In the fifth paragraph of his first great book Henry Miller says “I am the happiest man alive.” I for one believe him. He lived astutely aware of the incredible sickness and despair that surround us – the cultural despair derived from the pain in every sector of modern life, a pain indefinable but horribly real. His happiness was like the happiness of a man given a clear diagnosis of the intractable disease. Knowing this leads to the almost hysterical sense of release found in Henry’s books – the relief and joy of not being caught in the huge ailment. With his certain knowledge he was able to lead the kind of life he wanted. Happiness may be a major mode of therapy, but that is only incidental. Happiness was Henry Miller’s way of being in the world.

While his books denounce the sources of 20th century malaise, the nucleus of Miller’s life is to be found in the art of his books, his commitment to writing his life – the humorous memoirs, the lengthy perorations and jeremiads, the detailed descriptions of Parisians and New Yorkers and Greeks, the comedic sexuality, the commentary on the countless books he had been reading, and finally in the water color paintings. What happiness! – it incorporated anger, rage, and grief, that mammoth intellectual curiosity and the love of color in water trailing across a piece of paper. No wonder that to read him and to look at his painting makes people happy. Those who love his work may be among the happiest people alive.

Lee Perron

May 26, 2005

Just do it, Henry!

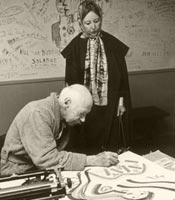

I became Henry Miller’s last art dealer quite by chance. After purchasing the Coast Gallery Big Sur in 1971, I discovered a cache of Henry Miller paintings, prints, books and letters in one of the storage vaults at the gallery. Miller had lived in Big Sur from 1944 to 1963 and had exhibited his paintings at the gallery continuously since its opening in 1958. I drove to his Pacific Palisades home to return everything. Upon approaching the front door I was stopped cold by a Chinese proverb taped to the door:

“When a man has reached old age and has fulfilled his mission, he has a right to confront the idea of death in peace. He has no need of other men, he knows them already and has seen enough of them. What he needs is peace. It is not seemly to seek out such a man, plague him with chatter, and make him suffer banalities. One should pass by the door of his house as if no one lived there.” — Menge Tse

I hesitated for the longest time, then with considerable trepidation, I knocked softly on the door. A stooped, frail-looking man dressed in pajamas and bathrobe opened the door and, speaking from one side of his mouth, he asked, “What can I do for you?”

I nervously explained who I was and pointed to the bulging art portfolio under my arm. He look surprised and in a graveled voice with a heavy Brooklyn accent, he declared, “But nobody ever brings anything back, don’t ya know?”.

Henry Miller invited me inside for what turned out to be a fascinating afternoon of hot tea and warm conversation. He spread out the watercolor paintings on his ping-pong table and examined them one by one: “Mmm,” he would mutter and, between deep-throated chortles, ooos and aahs, he would exclaim, “Mmm, not too bad, don’t ya know, did I do that?” Each observation was an excited rediscovery of paintings done years before. At the end he said, “well young fella, now that you’ve brought ‘em back, you better take ‘em back up the coast to the gallery and sell them–I need the dough!” And that’s how, thirty years ago, I became Henry Miller’s last art dealer.

Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer (Paris,1934) begins with a manifesto rich in disclosures and in promises:

“I have no money, no resources, no hopes. I am the happiest man alive. A year ago, six months ago, I thought that I was an artist. I no longer think about it, I am. Everything that was literature has fallen from me. There are no more books to be written...This is not a book. This is libel, slander, defamation of character. This is not a book in the ordinary sense of the word. No!

This is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of Art, a kick in the pants to God, Man, Destiny, Time, Love, Beauty...What you will. I am going to sing for you, a little off key perhaps, but I will sing...”

And sing he did for almost fifty years, in books, essays, pamphlets, letters, and in hundreds of gloriously free watercolors.

The range of his work is enormous, and the quality of the writing, though uneven, is always vigorous,exciting, direct in its insistence on a truth independent of fact.

His work is a permanent testimony to his determination to bring into the open all that is human experience; to open doors to the hidden inner life, and the hypocrasies and cruelties of life in the world.

His call is ever the same, ever meaningful - “wake up from your dream and begin to live.” he has kept the promise of his 1934 manifesto.

– Anonymous –